Few things get my blood boiling like hearing, “the 2020 election was rigged,

Sleepy Joe Biden is a total disaster, the far left radicals love criminals but hate

the police, or illegal immigration is destroying America.” In one fell swoop,

you have insulted my intellect, my judgment and my people. You have

misrepresented my viewpoint. You have questioned my basic values. You have

put forth a vision of the world that scares me.

Hmmm…. I’ve certainly put myself in a quite challenging position, one where a

single political statement takes me down a well-worn path that always ends in

visions of Armageddon and existential dread. I think to myself, “This can only

mean one thing. This far right insanity is going to spread and the world will not

be a safe place for me and those I care about.” Talk about catastrophic

thinking!

But if I’m so sure I’m right, then why do I feel threatened? And why do I feel

especially threatened when the comment comes from someone I love and

admire? Is the real fear that I am wrong? Is the real fear that the beliefs and

values on which I’ve built my entire life are not the only valid ones? Is the fear

that out of the 7 billion or so people on this planet that possibly my opinion

alone is not the right one in every single way? Is it possible that my

experiences in this life are so remarkably representative of the “human

experience” that there is no need for further exploration, no need to hear about

others’ personal experiences? Or maybe the real fear is that hearing another

viewpoint might change my mind and I’d then have to question everything I’ve

built my life around?

Maybe our 4th principle can give us some guidance here. Our 4th principle

supports “a free and responsible search for truth and meaning.” Which aspects

of ourselves represent our “truth”? Is it our beliefs about the origins of the

universe and the existence of a divine being or beings? Is it our sexuality and

gender identity? The type of music we love? The type of career we pursue? Our

friends and family? Our hobbies? Our faith? Our past? Our goals and dreams

for the future? Our political beliefs? Or do perhaps all of these are aspects

come together to form our own personal truth and meaning?

If we truly believe we are here to support one another’s “free and responsible

search for truth and meaning,” if we want the freedom to be vulnerable among

friends, if we want others to feel comfortable being vulnerable in our presence,

if we want to create a true sanctuary of the spirit, then we need to allow one

another to bring our full selves to this fellowship. We need to allow for a

diversity of views. We need to allow others to share their darkest moments,

their past mistakes and their present truths without shame or embarrassment.

We cannot deny members of our congregation the right to define themselves in

all ways – including political. If you’ve ever been to relationship counseling,

you may have heard that “scorn” or “contempt” are deadly to relationships.

You cannot be disgusted by someone, you cannot see someone as less than

human or less than you and still maintain a loving relationship with them.

Here at BUUF, here in the UU tradition, respect and compassion are at the

core of what we do. Rev. Anya Sammler-Michael of the UU Congregation of

Sterling puts it this way, “The main point of our free faith enterprise is

encouragement of different views – an honest and open engagement in a

compassionate space. If we sacrifice that and ask people to be hypocrites – to

give up a piece of themselves if what they are is different politically from the

norm – then we sacrifice everything that makes our congregations sacred

ground. We sacrifice our capacity to practice the beloved community and

therefore we sacrifice our capacity to learn how to do it in the world at large.

Could we [instead] see our willingness to be with one another even, and

especially when, we do not agree, as our most profound blessing?”

One great insight of many Asian religions is that Ying and Yang are not

enemies and that the dark and the light exist together in the same space. For

example, consider these opposing truths: Welfare helps people who have

legitimate challenges supporting themselves AND some people commit welfare

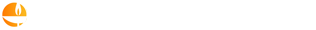

fraud. MLK, Jr. was a great leader AND a womanizer. America’s founding

fathers created a more equal form of government AND oppressed women and

slaves. The Buddha abandoned his family AND helped release millions from

suffering. Humans are the product of both nature AND nurture. Capitalism has

fostered innovation and AND inequality. There are a lot of good causes AND

there is not enough time or money to address them all. And yet it is very hard

for any human mind to accept that two opposing realities can both be true at

the same time. We work to eliminate uncertainty at all costs, even if it means

ignoring or severely downplaying one opposing reality in favor of another.

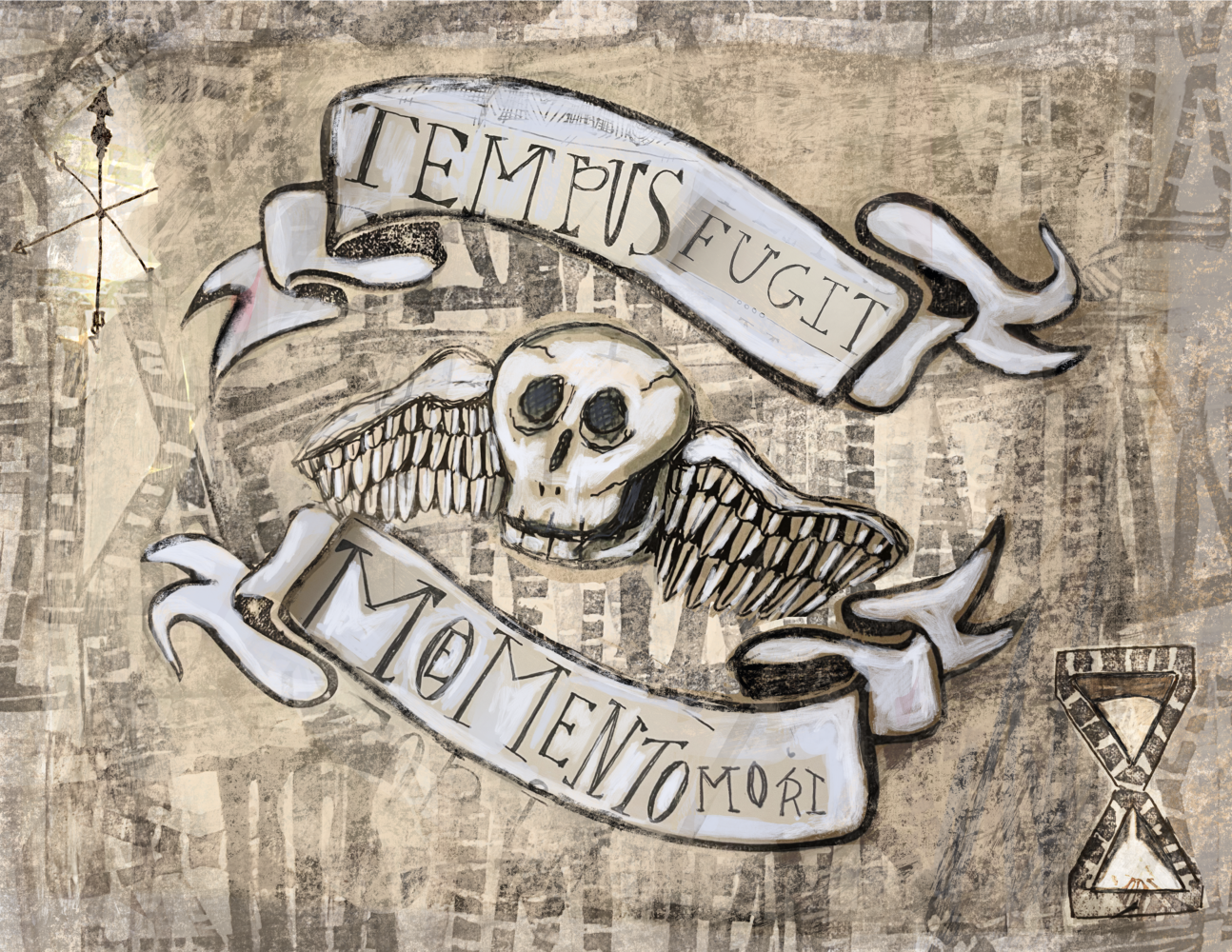

In essence, we are clinging to our sense of certainty, to our sense of security, as

if learning we are wrong or even that the truth is more complicated than we

are willing to admit will be the end of us and the end of the world as we know

it. And maybe it will be, because after all the only world we know is the one we

hold in our minds, our stream of consciousness, our unconscious paradigms.

But we are assuming that it will be the end and not a rebirth or a fine tuning of

our perspective. We enjoy hearing experts and famous people agreeing with

our views and denouncing those with opposing views without realizing that this

desire for certainty and approval, this avoidance of fear, makes us vulnerable

to biased thinking and manipulation. Rather than strengthening our minds, it

weakens them, not to mention how it weakens our relationships and our

society.

On the other hand, the only real truth, according to the Buddha, is

impermanence. When we cling to earthly desires, such as approval from our in-

group, political power and self-righteousness, we are setting ourselves up for

suffering. Cravings like these may bring immediate pleasure but also reinforce

our enslavement to a fragile world. Rather than relying on echo chambers and

partisan news outlets to shore up our feelings of security, of righteousness, we

could choose instead to embrace ambiguity, to recognize that the truth is often

contradictory and multi-faceted. We could choose to detach from our desire for

certainty and to remember that everything changes, even our politics.

The Buddha said, “Those attached to perception and views roam the world

offending people.” More recently, the Vietnamese Buddhist sage Thích Nhất

Hạnh (Teek Nyaht Hahn) wrote in his book Being Peace, “Humankind suffers

very much from attachment to views.” It is possible to advocate for what we

believe is right without becoming emotionally attached to it, without clinging to

it for dear life, and while maintaining great compassion for both ourselves and

others who are also seeking certainty and also struggling with detachment.

We would all do well to remember that many of our most passionately held

views come out of our own unique experiences, our own unique biology, and

possibly our own deepest fears. And we might choose to remember that other

people’s political views say more about their fears and anxieties than our own.

I might not agree with my friend about taxation or student loan forgiveness, but

we can still work together at the soup kitchen.. And I can help create a

sanctuary at BUUF where others feel it’s okay to be vulnerable, to admit their

struggles with addiction or to come out as gay, Christian or even – gasp –

Republican.